Canada’s Health Care: Lessons from Abroad

Canada’s health care system is facing a crisis—long wait times, limited access, and growing frustration among patients and providers alike. But what if we could learn from countries that have already solved these problems? This report takes a close look at how nations like Australia, Germany, and Japan manage to deliver universal health care with faster service and better outcomes. Drawing from The News Forum’s insights and a revealing look into Japan’s efficient system, it explores practical solutions Canada could adopt to ease patient suffering and finally get our health care system back on track.

Overview: The News Forum’s “Health Reform Now” report asks whether Canada can learn from other countries’ universal systems to reduce wait times and “stop patient suffering”. It notes that nations in Europe and Australia have figured out how to provide universal coverage with shorter queues. In fact, analyses show Canada performs poorly on access: for example, in 2020 only 62% of Canadians waited under 4 months for elective surgery, versus 99% of Germans and 94% of Swiss patients. This suggests real opportunities for reform.

Key solutions from Europe and Australia: Observers identify several policy changes that could improve

Canadian care, drawn from high-performing systems. These include:

- Leverage private-sector delivery. Allow privately-run clinics and hospitals to treat publicly-insured patients. In Australia’s mixed system, roughly half of hospitals are privately owned, and about 70% of elective surgeries occur in private facilities (but funded by the public system). By contrast, Canada now bars most private delivery. Emulating Australia (and similarly Germany/Netherlands) could expand capacity without raising taxes.

- Permit regulated private insurance/payments. Encourage patients to purchase supplementary coverage or pay directly for timely care. For instance, Germany allows citizens to buy private insurance or pay out-of-pocket for faster access even while maintaining universal coverage. Switzerland mandates basic private insurance (with subsidies for low-income families) alongside its public system. Such models create competition and options, and have been shown to speed up access. (The Fraser Institute notes Canadians want such flexibility.

- Reform hospital funding and introduce co‑payments. Move from fixed global budgets to activity‐based funding, and consider modest patient copayments. Many OECD countries pay hospitals per procedure and require patients to share a small portion of costs. This motivates efficiency and helps manage demand. For example, Australian and European systems generally require low-level copayments (or insurance premiums) to complement public funding. By contrast, Canada’s no‑copay, block-budget model offers few incentives to clear queues.

- Expand provider supply and reduce barriers. Canada could make it easier for qualified providers to open new clinics and perform insured services. Unlike Canada, some jurisdictions explicitly encourage new capacity: for example, Japan publishes fixed fee schedules and lets any qualified clinic or hospital enter the market and receive payment. Even in Europe, easing licensing and allowing more nurse practitioners or doctors (as Australia has) boosts supply. Adopting similar deregulation in Canada would help reduce bottlenecks.

By combining these reforms – more public/private partnerships, patient choice, demand management, and expanded capacity – Canada could more closely match the performance of its peers. In high-performing systems, such changes have correlated with far shorter waits for routine care (e.g. same-day doctor appointments and specialist referrals for the majority of patients.

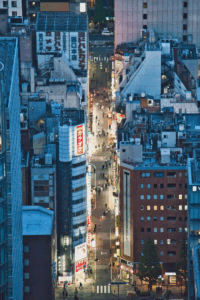

Figure: Modern clinic hallway (representative of improved facilities). Many experts argue Canada should allow similar private or mixed clinics to handle publicly-funded care, as in Australia’s health system

Japan’s Universal System: Virtually No Waiting Lists

In Japan, the health-care system achieves “virtually no waiting lists for any forms of treatment”. This is the result of very high capacity and open access. Japanese patients see doctors about twice as often as the OECD average and hospitals run five times as many MRI/CT scans – yet waits remain negligible. Japan’s universal insurance (in place since the 1960s) sets all fees and then lets any qualified public, private non-profit or commercial provider deliver care at those prices. There is no restriction on opening new clinics or private hospitals if staff are available. As a result, roughly 70% of Japan’s 8,000+ hospitals and 95% of its 100,000+ clinics are privately owned, creating intense competition and abundant capacity. (By contrast, Canadian governments actively limit provider numbers and often ban private-pay options.

Because patients pay only minimal copayments (around ¥3,000, roughly US$28, for a doctor visit while the government covers most costs, demand is met quickly. Critically, Japanese planners also cap patient outlays for expensive procedures (a heart operation, for example, has a copay cap of ≈¥300,000, about $2,500. These features ensure even major surgeries and diagnostics can be scheduled promptly. In practice, Japanese hospitals typically see urgent cases immediately and non-urgent cases within weeks – rarely more than a month. In short, Japan’s blend of universal coverage, high provider supply and government cost-control yields a responsive system with virtually no queueing.

Beyond supply, Japan benefits from healthier population habits (fewer chronic diseases) and use of technology, but the core lesson is structural: grow capacity and share costs. Allowing many providers to operate under a single insurance scheme – while regulating prices – avoids the logjams seen in Canada. As one Canadian analysis concludes, “Japan’s approach is the complete opposite of Canada’s” with respect to supply, explaining why Canadians could learn a lot from its model.

Sources: The above analysis draws on policy research and expert commentary. It cites The News Forum summary, Fraser Institute studies of wait-time differences, and detailed comparisons of Japan’s system. All statistical claims and quotations are from these sources.

The News Forum | Health Reform Now

https://www.thenewsforum.ca/healthreformnow

Other countries with universal health care don’t have Canada’s long wait times | Fraser Institute

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/other-countries-with-universal-health-care-dont-have-canadas-long-wait-times

Canadian policymakers should learn from Australia’s health-care system | Fraser Institute

https://www.fraserinstitute.org/commentary/canadian-policymakers-should-learn-australias-health-care-system

FINANCIAL POST COLUMN: Japan — land of no health-care wait times – SecondStreet.Org

https://secondstreet.org/2025/08/28/financial-post-column-japan-land-of-no-health-care-wait-times/

How does Japan deliver so much healthcare so efficiently? | Global Japan Lab

https://gjl.princeton.edu/events/2025/how-does-japan-deliver-so-much-healthcare-so-efficiently